The power and convenience of the Internet and the Web are so attractive that we forget there is a price we pay for using them. And generally we are willing to pay that price. But sometimes we are lazy and forget to ask the price or we don’t understand how high a price we are paying. A good example is the “free” email services such as HotMail or Gmail. When you sign up for them they warn you that Microsoft and Google, respectively, own the content of what you send. Recently a bunch of people have sued Google because they learned that Google was scanning their emails and—it is alleged–using the information not only for targeting advertising to the Gmail users but also using it for secret profiles of these users. This practice is a good example of the “Intentional Blooper” we just cited. The antidote for email users is to pay a bit to email services who guarantee not to use the information.

Monthly Archives: March 2014

Is Google’s Picture Gatekeeper Simply Capricious?

Do other mere mortals attempting to set up pictures for their new YouTube channels or avatars for their new Gmail accounts have the same troubles we have been having? Or do they want to discourage users other than advertising customers from having graphics? Or what? For starters, there is no initial guidance given as to desirable or acceptable ranges of pixel counts. (Does Google not believe that we mere mortals know what a pixel is?) Then when we try one of our set of pictures with different resolutions, the gatekeeper deems it too high resolution. On the next try, it is rejected for being too low resolution but now it tells us what the lower limit is so on our third try it is accepted and we drag its corners to fill the target provided. Success! Nope, now the gatekeeper plays another one of his/her tricks. For the YouTube channel picture he/she decides to crop it, apparently to some resolution du jour. For the Gmail account he/she instead says that he/she can’t set it up today so try again later. Huh?! Are Google’s computers tired or something?

Unintentional and Intentional Bloopers

Probably you think of a blooper as a one-time mistake, the sort of often-humorous slip (often called an “out-take”) that an actor or public speaker might make. In recent years it has become stylish for some movies to tack on the best of these after the final scene. In high-tech hardware a blooper is usually a costly mistake, because the product malfunctions and has to be replaced. Ditto for software with critical missions—military, industrial control, etc.—or for gaps in security that offer hackers a chance to cause costly mischief (the late 2013 theft of Target’s credit card customer data comes to mind). Fortunately, for a lot of the content on the Internet, especially the Web, such mistakes are frequently more annoying than costly.

But there is a lot of stuff on the Web that isn’t what it seems to be, and intentionally so. Why? Because of the vested interests of the companies and individuals providing it. Hardly anyone believes that all advertising claims are true, but they aren’t on the lookout for intentional shady behavior motivated by billions of dollars of economic gains. People are now starting to realize that the big information companies like Facebook and Google are using harmless-appearing personal data (which they thought was being held in confidence) for purposes never imagined. People who clamor for “transparency” in government and elsewhere aren’t yet clamoring for it in such areas as search engine rankings. TechnologyBloopers will identify these “Intentional Bloopers” so the public can pressure the violators to fix them.

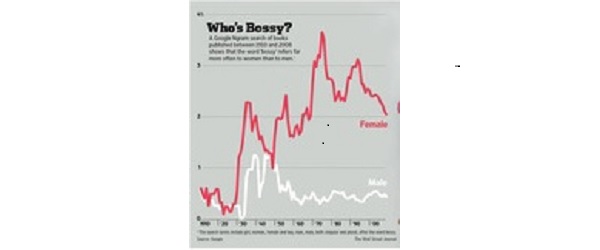

Be Careful When Using Any Google or YouTube Search Quantitative Results

There are scattered comments criticizing the criteria (and changes in them) that Google uses to include, and especially to rank, the results of their searches. It is tempting—but risky–to use these searches to quantify trends. And we are not even sure that Google itself understands that this is happening. Given the origins of Google, and some of their early goals, we doubt that Google intentionally is trying to mislead people who use their Ngram search, though their using vague terms to describe the number of documents is highly suspicious. In any case, ethical scientific practice requires that findings are REPRODUCIBLE. In the case of the Don’t Call Us Bossy article in the Wall Street Journal (a publication that should know better), which listed the search terms, it was not possible to arrive at a set of curves that showed the first peak in the curves during the 1930s, and there was thus no basis for the authors to draw any conclusions about the trends in that time frame. The amount of bossiness in the 1930’s is not the point here; the point is that we should be very careful to validate any supposed trends beyond just what Google searches indicate.

Let’s Demand Correct and Useful Technology

The latest developments in computing hardware and software continue to produce miraculous functionality. But it could be a lot better if the numerous mistakes or misguided directions in design and implementation were fixed. Technology Bloopers is a forum for calling these mistakes to the attention of the companies and individuals making them, and asking that they be fixed. We’ll not only point them out, but insofar as possible point out paths to improvement.